Was Will Munny ever saved?

That’s the question at the heart of Unforgiven. I don’t think the film is as perfect as many seem to find it—Eastwood biographer Richard Schickel calls Unforgiven the greatest Western ever made, a hyperbolic statement if I’ve ever heard one, given a) the quality of the best Westerns and b) the deliberately understated tone of Eastwood’s final Oater (it means to elegize the genre, not top it)—and it is that central question about Munny’s true nature that (intentionally?) gives me most pause when assessing my own feelings about the film.

One could argue that Eastwood has elided an important stage from Munny’s development. As it stands, the antihero has two faces: contrite and vengeful. The former face takes up roughly 110 minutes of the 130-minute film. The operative word here is “reformed”; Munny talks, and talks, and talks about how he isn’t the same man, how his dearly departed wife saved him from a life of drinking and mayhem, how the monster that killed “just about everything that walk[ed] or crawled at one time or another” is no more.

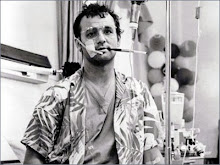

His reformation permeates every atom of his being—being good has made him impotent. Munny can barely shoot, passively suffers a vicious beating at the hands of Gene Hackman’s Little Bill Daggett, and, most literally, refuses a complimentary roll in the hay courtesy of the prostitute whose scarred face sets the plot in motion. Our first good look at Munny—he’s crawling around in the mud, trying valiantly, and failing, to control the livestock in his beyond-hardscrabble pig farm—could not better depict the degradation that the wages of sin, and of redemption, have cost him.

And then Munny gets word that Daggett has murdered Ned Logan, his only real friend and the closest thing Munny has to a conscience, and Munny transforms into the Angel of Death. Strides into Big Whiskey like a spirit. Kills everyone that needs killing without so much as suffering a scratch. Intimidates those still breathing through sheer force of will. And then, vanishes. Maybe back to his farm, maybe to San Francisco, maybe to whatever plane of existence that loosed The Drifter from High Plains Drifter or Preacher from Pale Rider, who knows. Whatever the case, Munny is gone, his last (?) bloody shootout an affirmation of his true nature, of the sins of the Old West.

It goes without saying that Eastwood is splendid in both facets of the character. That much is certain. Redeemer Will is a pathetic deflation of the Western icon we expect; the Angel of Death inflates that icon to the point of abstraction—his brutal precision is as alien as it is exciting.

But there is no in-between. Whatever bridge one might normally expect, Eastwood perversely denies us. One minute, Munny is decrying killing to the battle-shocked Schofield Kid, and the next, he’s coolly savaging six people. We don’t see the progression, the return of one man from another. We see one man. Then we see the other.

The more I process this, the more I respect it. Clint has oft trafficked in ambiguity, and this might be the most complex iteration of it in his oeuvre. Was Munny redeemed? Is he trying to force it—his constant proclamations of his lack of wickedness ring the “Me think he doth protest” bell loud and hard. If he reverts back to his old self at the end, does he stay that way, or does he start a new, happier life with his children in San Francisco? Is that final epigraph more than a rose-colored conjecture? Is Munny even “bad” in the final shootout—he is spurred on by the death of the most morally sound character in the film, after all.

It’s a slippery resolution for a slippery character. Everyone else in the film is at a certain peace with his or her contradictions, from Little Bill through Strawberry Alice. Will Munny seems to exist outside his ambiguities, and his distance from himself obfuscates matters irrevocably.

With Eastwood’s film, we get a view of violence and death unlike any I have ever seen. I don’t know if it is as narratively and emotionally satisfying as a (slightly) more concrete take on Munny might be—seeing Will evolve into the man he was would have a savage inevitability. As it is, the film lacks the weight of tragedy. Nothing is inevitable. It just is.

There’s something much more disturbing about that, I reckon.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment