The phrase, “High-concept film,” carries a certain negative stigma, and with good reason. If you can boil down a movie to its most reductive, implausible elements, then chances are it lacks some measure of subtlety, nuance, originality. Off the top of my head:

1. A street-smart seven-year old teams up with a grizzled cop to solve a murderer. BULLSHIT.

2. A single father tries to get closer to his children by posing as their elderly British nanny. BULLSHIT.

3. A team of roughneck oil drillers stands between life and total annihilation in their efforts to destroy an incoming asteroid. BULLSHIT.

Of course, in high-concept films, as in life, there are always exceptions. A reclusive billionaire becomes engaged in a life-or-death battle against a grizzly bear. Two career criminals with hostages in tow find themselves holed up in a vampire-run strip club. A team of globetrotting thieves steals corporate secrets from the recesses of the human brain. The Secret Service agent who failed to save JFK has to unravel an assassination plot against the current president.

That last one is the premise of In the Line of Fire, which remains one of the great high-concept romps of the last twenty years. Is the film believable? Not remotely. Does it matter? Not a whit. The film is made with such flair that it’s easy to suspend disbelief; it does what it wants to do so well that you go along for the ride without hesitation. In its own way, In the Line of Fire is a perfect film.

It’s the conviction of the film that sets it apart. Essentially, it follows that old standard, that great and venerated and hoariest of action movie conventions—the aging hero given a second shot at redemption—and yet director Wolfgang Petersen and his crew approach the topic with…something resembling dignity. Characters seem…smart. The script doesn’t make them act out of character for convenience’s sake or to kick the plot into overdrive.

I keep coming back to a scene late in the film. Clint Eastwood’s douchebag commanding officer has booted him from the assassination investigation following a very public snafu. Unsurprisingly, Eastwood discovers a key piece of information at the zero hour, and we viewers expect a scene where his CO dresses him down and ignores the intel, forcing Clint to go rogue to save the day.

Except that doesn’t happen. Eastwood lets his boss know what he’s found out, and his CO immediately grants him access back to the case. The film constantly sets up its audience like that, promising a cliché before doubling back with some genuine human behavior.

Even the most potentially-groan worthy subplot, the budding romance between Clint Eastwood’s Frank Horrigan with fellow Secret Serviceman Rene Russo, has spark and grit and humor. It’s not Tracy and Hepburn, but it’s closer than most similarly minded subplots get.

Petersen frames his Secret Servicemen (and one Secret Servicewoman) with crisp professionalism. He peppers the film with little behind-the-scenes asides, showing us how they prep an area for a Presidential speech, or how they delegate duties down the chain of command, and those bits of business lend a welcome verisimilitude to his heroes. They respond intelligently to all the implausiblities chucked at them, and should they falter…well, then they weren’t playing the game as well as lead psycho Mitch Leary (John Malkovich).

However, if In the Line of Line gerried all that and only nailed the interactions between Eastwood and Malkovich, it’d still be pure pleasure. Both men are so good, their interactions so tense and primal and funny, that they elevate the whole piece.

Watch the scene where Leary badmouths JFK’s favorite poem, “I Have a Rendezvous with Death” in taunting conversation with Eastwood’s Frank Horrigan. There’s so much to feast on here, Malkovich’s improvisatory wit mingling with genuine menace, Eastwood’s subtle disgust and agreement with Leary’s put-down, and it’s emblematic of their whole screen-relationship.

Malkovich gets the most credit these days, and it’s not hard to tell why. His Academy Awarded-nominated ex-CIA spook-turned-off-the-reservation-whackadoo competes with Alan Rickman’s Die Hard baddie for Most Influential Action Movie Villain of The Last Fifty Years.

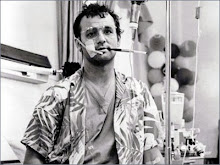

But rewatching Eastwood was revelatory, especially given this role’s place within the context of his career. Not only does he turn in a bonafide STAR PERFORMANCE, the kind of thing we used to expect from Cary Grant or Humphrey Bogart or Sean Connery, but he hits some notes he’s never sounded before, or since. His Frank Horrigan invites comparison with all the taciturn badasses he’s ever played, from Harry Callahan through Walt Kowalski, but there’s a subtle change here. Horrigan is jaded without being cynical, tough without being brutal, quiet without being taciturn, funny without dipping into gallows humor.

There’s a real lightness to his work, a nimbleness of character, that is utterly delightful, almost as if Clint is sending up his Badass Persona while simultaneous painting another shade on the real thing. The effervescence in his performance is especially astounding when one considers he shot this film almost back-to-back his tortured work as Will Munny in Unforgiven.

This is the film The Rookie should have been. Smart, funny, thrilling, and utter bollocks.

In short, a delight to teach.

Monday, September 6, 2010

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)